Is Geology Cartesian?

Contents

Is Geology Cartesian?¶

Geocomputing is about processing and interpreting geo-data, realizing physical simulations and solving inverse problems. All these tasks somehow call for approximating time and space by discrete points, some associated values, and the neighborhood relationships used to connect these points.

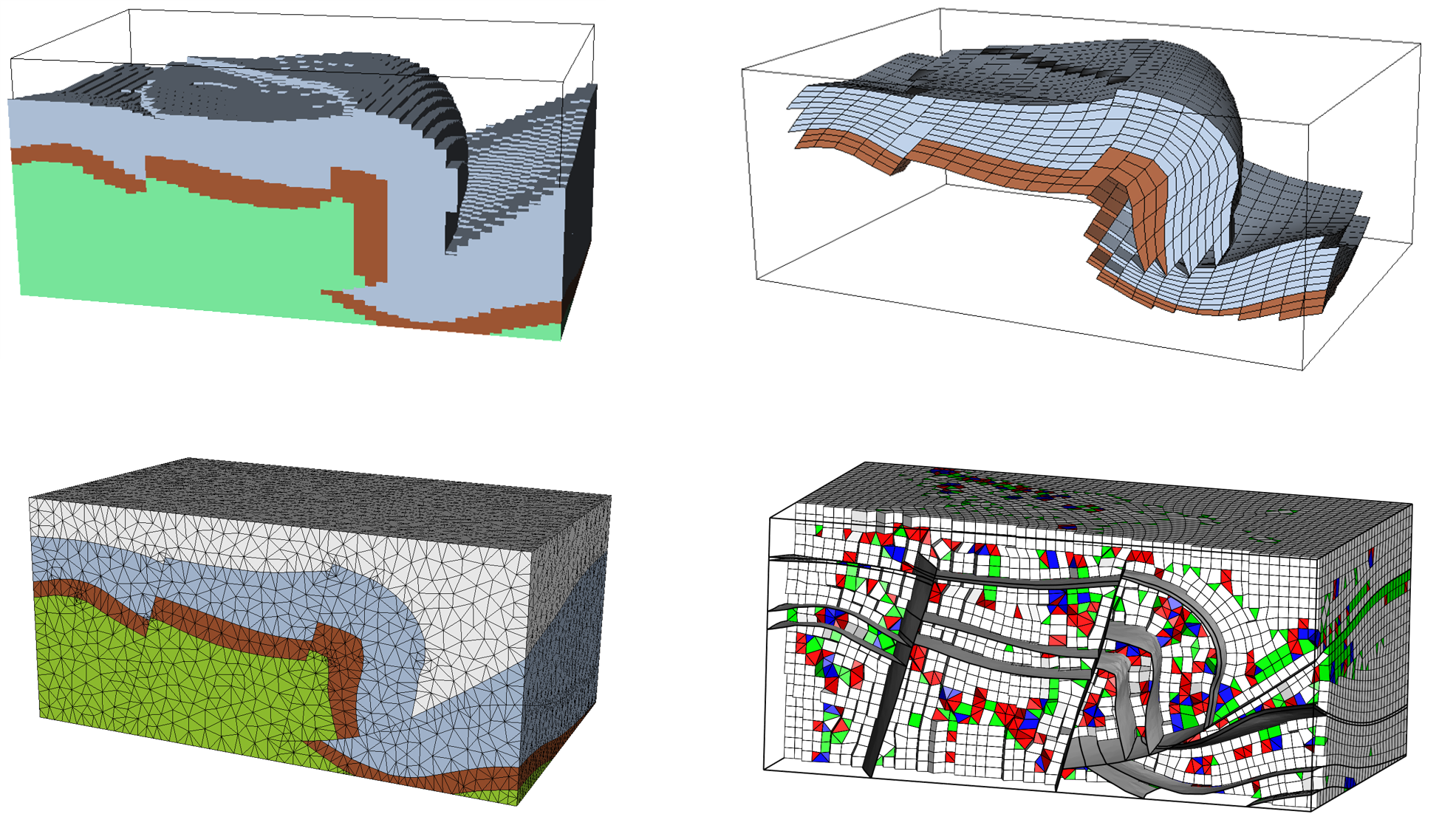

Grids typically implement these principles, but which grids should be used in geocomputing Figure 1? Cartesian grids have many qualities, owing to their structure and regularity. Neighborhoods are trivially defined. Many great image processing algorithms, geophysical methods, geostatistical algorithms, and other useful numerical techniques directly apply to Cartesian grids. A computer screen is a grid. Most computations in reflection geophysics use Cartesian grids, and produce excellent images of the subsurface.

Yet, a vast community of geoscientists and physicists, not only in the academic world, has spent much effort to develop codes on irregular and unstructured grids. For example, reservoir engineers and hydrogeologists use deformed Cartesian grids (also called corner-point or geocellular grids, see for instance DUMux). The bravest use fully unstructured grids (made of tetrahedra, prisms or even arbitrary polyhedra). From a programming standpoint, these grids are scary. Many of the efficient algorithms designed for Cartesian grids fall apart when considering irregular geometry and arbitrary connectivity. Parallelization remains possible, but is more difficult to implement. Still, in addition to commercial software, several open-source packages exist nowadays to work effectively with unstructured grids, for example:

Generic meshing and geometric libraries: TetGen, GMSH, Geogram, MMG, CGAL.

Numerical simulation packages for generic computations such as Moose, FreeFEM, MFEM, or specialized such as OpenFOAM in fluid dynamics or SeisSol in seismology.

Integrated geocomputing platforms: OpenGeoSys , RINGMesh, OpenGeode.

Fig. 1 Four possible meshes representing the same geological structure (a thrust fold in Corbieres). Courtesy of Arnaud Botella.¶

Why did unstructured grids come up? This may be explained by some fascination for pretty pictures and a form of mathematical beauty of these meshes. But there has to be something else to justify investment in the business and engineering world.

We suggest that a stronger reason holds in the classical quote attributed to Albert Einstein: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler”.

Geometry / discontinuities¶

Geological processes are a tremendous engine to create geometrically complex changes of physical parameter fields; these changes can be quite abrupt, as two rock samples 1cm away one from another may have been formed million years apart [WC18].

Such sharp geological features may have arbitrary geometries, which is generally approximated in Cartesian grids as stair-steps. This may (or may not) be a problem, depending on the application at hand. Explicit representation of geological objects can be essential to focus on geological details deemed important for a particular purpose. This is exemplified for instance in the area of fracture modelling.

Studying fracture growth, quantifying fault reactivation and displacement needs an accurate geometric representation. The connectivity of fractures is also a very important point when it comes to understand subsurface flow. As fractures seldom align on orthogonal directions and generally span multiple scales, their explicit representation is very useful at some point (e.g., Nick and Matthäi [NMatthai11]; Bonneau et al. [BCR16]).

More generally, an accurate geometric representation of subsurface geologic features is important to create benchmarks such as the SEAM benchmark models; homogenized parameter field on Cartesian grids can then eventually become handy [CC18].

Adaptivity¶

With Cartesian grids, the grid block size corresponds everywhere to the size of the smallest feature that you want to represent. This is generally fine in two dimensions (digital pictures have the same limitations and are still very good “digital eyes”), but raises significant computational challenges in three-dimensional domains. Moreover, the Earth remains mostly inaccessible to observations an hidden “details” may matter.

Practitioners, therefore, make compromises by averaging some (expensive) borehole measurements at flow simulation block scale; conversely, values away from observations are poorly constrained and are sampled using geostatistical methods, even in the areas where heterogeneity has little or no impact. With unstructured grids, the element size can vary according to the dimension of the features that matter (See for instance [SR05] for further discussions in seismology).

All in all, unstructured meshing technology, once restricted to CAD/CAM applications, has matured to handle realistic geometries of geological features. We believe this is now the right time to use these technologies to address longstanding geocomputing challenges.

References¶

- BCR16

Francois Bonneau, Guillaume Caumon, and Philippe Renard. Impact of a Stochastic Sequential Initiation of Fractures on the Spatial Correlations and Connectivity of Discrete Fracture Networks. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 121(8):5641–5658, 2016. doi:10.1002/2015JB012451.

- CC18

Paul Cupillard and Yann Capdeville. Non-periodic homogenization of 3-D elastic media for the seismic wave equation. Geophysical Journal International, 213(2):983–1001, 5 2018. [Online; accessed 2022-01-18]. URL: https://academic.oup.com/gji/article/213/2/983/4831486, doi:10.1093/gji/ggy032.

- NMatthai11

H. M. Nick and S. K. Matthäi. Comparison of Three FE-FV Numerical Schemes for Single- and Two-Phase Flow Simulation of Fractured Porous Media. Transport in Porous Media, 90(2):421–444, 11 2011. [Online; accessed 2022-01-18]. URL: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11242-011-9793-y, doi:10.1007/s11242-011-9793-y.

- SR05

Malcolm Sambridge and Nick Rawlinson. Seismic tomography with irregular meshes, pages 49–65. American Geophysical Union, 2005. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/157GM04, doi:10.1029/157gm04.

- WC18

Florian Wellmann and Guillaume Caumon. 3-D Structural geological models: Concepts, methods, and uncertainties, pages 1–121. Volume 59. Elsevier, 2018, [Online; accessed 2022-01-19]. URL: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0065268718300013, doi:10.1016/bs.agph.2018.09.001.