Hardware is hard: teaching geotech

Hardware is hard: teaching geotech¶

Everybody has gone through the debugging process on some script they’ve written. Add some print statements, maybe fire up a debugger, set some breakpoints, and eventually the offending line is tracked down. A commit, push, and pull request are now all that separates the world from your updated program. Now imagine doing the same thing with a piece of hardware. You design a circuit and sensor, order a printed circuit board, get some power supplies, and after everything comes in, hook it up. On that first flick of the switch, a massive cloud of smoke fills the lab. After some debugging of a different kind, you fix errors in your circuit and start the whole process over again. It’s slow, expensive, and even potentially hazardous. Now imagine that the hardware you designed is controlled by software you’ve written. This embedded hardware space is where all modern scientific instruments live and where few geoscientists are prepared to go.

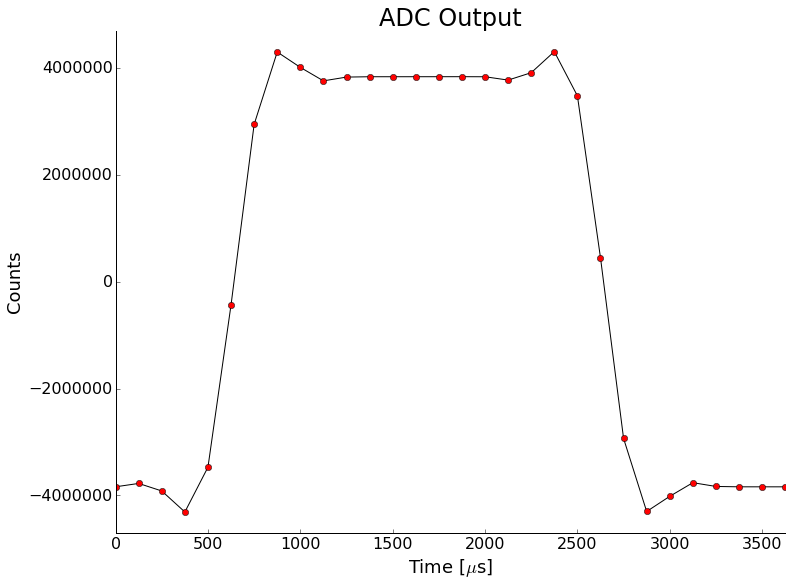

All data comes from somewhere. It could be a model constructed in a computer, laboratory measurements, field data, or some combination, but rest assured that hardware is required. In fact, misunderstanding the hardware can have serious implications. How is that sensor really measuring the magnetic field? Does temperature affect the readings? What kinds of filtering are being done before the “raw” data is collected and shown to you (Figure 5)?

Fig. 5 A simple example of an unknown filter in an analog to digital converter playing with data. The input to the system is a pure square-wave, but an on-chip FIR filter mentioned many pages back in the datasheet leaves artifacts that could be interpreted by the unknowing scientist.¶

Challenges like these often result in confused looks and the shrug of the shoulders from scientists, but as scientists we should be very invested in our data, from the moment it is measured to the last bit of electron shuffling we do to get the figures on paper. Inspired by this sentiment, I developed a course that was taught at Penn State to graduate geoscience students, as well as made freely available online (https://tge.readthedocs.io/).

Teaching any course is a lot of work, but this class turned out to be one of the most labor intensive tasks I’d tackle during grad school. In addition to the normal challenges of writing good exercises and developing lecture material, there were challenges of getting everyone to safely build circuits and operate shop equipment. One of the first lab exercises was drilling a hole in an aluminum plate and tapping the hole with 1/4” threads. I dutifully wrote up two pages of instructions, thinking I had covered everything, only to be greeted by students who didn’t know how to put drill bits into a drill press.

The background required for working with hardware is diverse, and only taught in high school shop classes, which are diminishing in number. Scientists in the field or lab need to develop skills that range from working with hand tools to basic electrical wiring, maybe even getting as advanced as designing simple circuits. As we’re always pushing the boundaries and trying new ideas, the equipment we need often doesn’t exist yet and we’re left to hack, modify, or design what we need. We then drive engineers mad with our order of magnitude reasoning that doesn’t help constrain a design.

For the class, I decided to use a class project to give students the experience and frustration of working with hardware. Students would get general lectures throughout the class, with occasional field trips to the machine shop, and homework assignments that were a combination of calculation and basic mechanical/electrical engineering with a smattering of Arduino based practical exercises that built on the homework. Sometimes the basic theory type lectures and assignments would get boring for the students, but the labs and projects allowed them to embrace the fail fast and often agile methodology – how R&D really gets done (Figure 6).

Fig. 6 Students participated in a variety of laboratory exercises, including learning how to calibrate sensors such as load cells and displacements transducers. In the activity, they began to get a real understanding of instrument error sources.¶

So, what should you take away from this? Next time you use data, try to learn about how it was collected. Maybe buy an Arduino kit and play with taking readings from sensors, learning how physical quantities we want to measure turn into voltages, that turn into quantized digital representations of voltage, that we then turn back into physical quantities through a series of calibrations. Don’t get discouraged, hardware is hard, but knowing enough to help troubleshoot or modify a piece of gear is likely to come in handy and will become a more sought after skill as time goes on!