SEG-Y: Judging books by their covers

SEG-Y: Judging books by their covers¶

The Society of Exploration Geophysicists seismic data exchange format (SEG-Y) shares a lot of similarities with books. All books have a cover and a series of numbered pages, each of which contains text or pictures. Similarly, all SEG-Y files have file headers, trace headers, and data traces.

A publishing industry has emerged that oversees the exchange of information via books. This industry has conventions around information encapsulation that includes cover formats, blurb location, ISBN’s, and author attribution. Without exception, every book publisher follows these conventions.

The geophysical industry lacks a similar orthodoxy around the data encapsulated in SEG-Y files. Unsurprisingly, this makes reading poorly documented seismic data near impossible. Why has such rigidity in our industry’s norms failed to materialise?

The reasons for this are many and varied. The textual header format recommended is well suited to North American data. But the standard has not kept pace with the variety of datatypes using SEG-Y. Most software outputs generic textual headers with little default data context or opportunity for change. Data creators don’t understand how important it is to correctly encapsulate their data, and data recipients fail to demand higher standards. All of these issues are fundamentally behavioural and will not disappear by moving to a new data standard. People have criticised SEG-Y as an archaic format, but most reported issues can be solved by rejecting the idea of exchange as an ad hoc data transfer and embracing a data publication mentality.

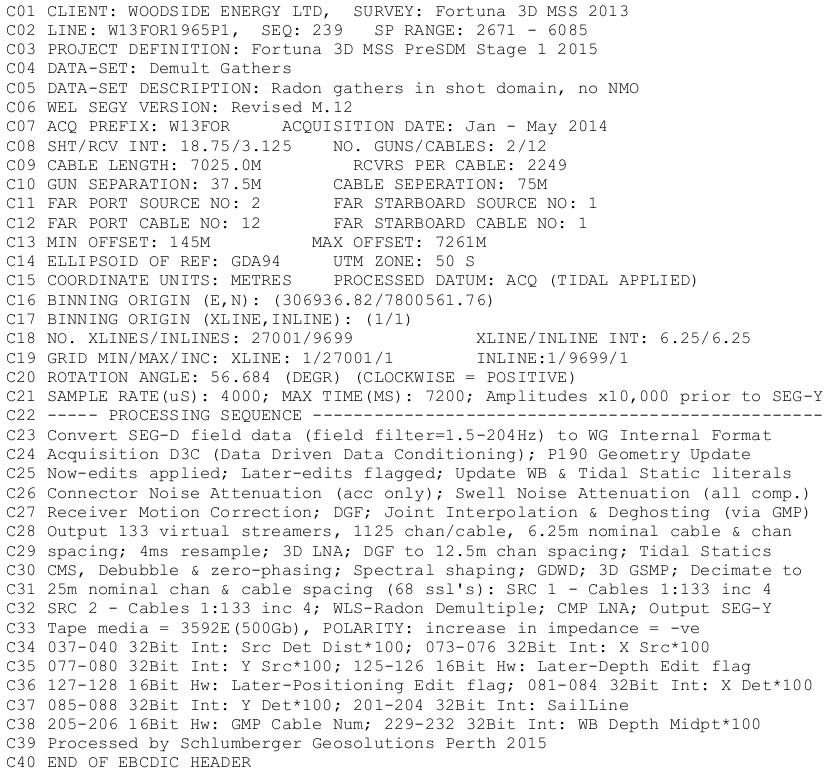

The very first thing to read when loading a SEG-Y file is the textual header, so this header is akin to a book cover. All books regardless of their type have the following on or near their cover: a title, a blurb, author, a publication location, a language, the publisher, and a statement of copyright.

Similarly all SEG-Y textual headers need similar:

Title: Dataset summary (4-5 lines). This section contains at a minimum, the survey/well name, general location of the data, permits ingressed, data type, and data extents.

Blurb and author: Dataset history (15-20 lines). This section contains everything that has been done to this dataset since it was acquired and who did it. It generally includes a number of sections: acquisition, processing, imaging, post-migration data conditioning, calibration, inversion.

Publication location: Dataset CRS and geometry (4-5 lines). This contains what coordinate reference system (CRS) the data uses, the corner points, and the bin spacing and extent of the 3D grid (or the shotpoint and CDP extent and relationship for 2D lines).

Language: Trace header description (4-5 lines). Trace headers in the file needs a label, a byte header location, and a format statement.

Copyright: Dataset owner and licence (1-2 lines). Is this data openfile, proprietary or multi-client? Who owns the data. Who can I contact about buying or using it?

An example of such a header is shown below.

Fig. 2 Add a figure caption here¶

The textual header is the canonical location of this information. Filenames are lost when data is transcribed to tape. Internal datamodels of geotechnical software rarely allow attaching reports and documents to seismic data. It is only by embedding this vital information in the most visible part of the file that you can be sure that is will be kept with your data, forever.

So how can you help? If you create seismic data files, take the time to write a complete header. If you are the recipient of seismic data, demand higher standards. Look at the textual header and ask yourself, “Is this a satisfactory summary of this data?” and, “Can this data be unambiguously read using only the information here?”. If the answer is No, send it back to the source and ask for it to be done properly.

We all judge books by their covers. Let’s make SEG-Y files people want to read.